Types of Arrhythmia in Children

Abnormal heartbeats, or arrhythmias, can also affect children.

Your child’s health care professional may ask you or your child questions if they have difficulty describing symptoms. You also may be asked about your child’s medical and family history. These answers can help establish your child’s risk for an arrhythmia. Diagnostic tests for abnormal heartbeats may also be recommended.

Types of arrhythmias in children include:

- Long QT Syndrome

- Premature contractions

- Tachycardia

- Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

- Bradycardia

- Sick Sinus Syndrome

- Complete Heart Block

Checklist for parents of children with arrhythmias.

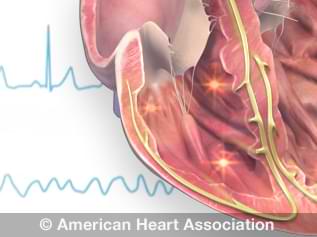

Watch animations of several types of arrhythmias.

Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)

Like other arrhythmias, Long QT Syndrome (LQTS) is a disorder of the heart’s electrical system.

When a child has LQTS, the lower chambers of the heart (ventricles) take too long to relax after a contraction.

The name for the condition comes from letters associated with the waveform created by the heart’s electrical signals when recorded by an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG). The interval between the letters Q and T defines the action of the ventricles. “Long QT Syndrome,” then, means that the time gap between these points on the ECG is too long.

LQTS can be hereditary, appearing in otherwise healthy children. Other children may acquire LQTS, sometimes as a side effect of medications.

Some arrhythmias related to LQTS can cause sudden cardiac arrest and are potentially fatal. Deafness may also occur with one type of inherited LQTS.

Symptoms of LQTS

Children with LQTS may not have any symptoms. Children who do have symptoms may experience:

- Fainting (syncope)

- Seizures

- Irregular heart rate or rhythm

- Fluttering in the chest

- Sudden death

Children with LQTS may have a longer-than-normal QT interval during physical activity, when startled by a noise or when experiencing intense emotions, such as fright, anger or pain.

If your child has fainting episodes, or if your family has a history of fainting or sudden heart-related death, LQTS should be looked at as a potential cause. Your child's health care professional may recommend an exercise stress test in addition to an electrocardiogram and genetic testing.

How is LQTS treated?

Treatments for LQTS in children include medications, such as beta blockers and surgical procedures such as an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

Your child’s health care professional may also limit any drugs known to prolong the QT interval. Other risk factors, such as an electrolyte imbalance, are best avoided as well.

Premature contractions

Premature or extra contractions are arrhythmias that can occur in children with structurally normal hearts. Premature beats that start in the heart’s upper chambers (atria) are called premature atrial contractions, or PACs. Premature ventricular contractions, or PVCs, start in the ventricles.

When a contraction in either chamber occurs prematurely, a pause usually causes the next beat to be more forceful. If your child or teenager says their heart “skipped a beat,” it’s typically this more forceful beat that caused that feeling.

Causes and treatment

Premature beats are common in normal children and teenagers.

Usually, no cause can be found, and no special treatment is needed. The premature beats may disappear on their own. Even if your child’s premature beats continue for some time, the condition is usually no cause for concern. No restrictions on your child’s normal activities should be needed.

Occasionally, premature beats may be caused by disease or injury to the heart. If your child’s health care professional suspects this may be the case, they may suggest more tests to evaluate your child’s heart health.

Tachycardia

Tachycardia can have various causes and refers to a heart rate that’s faster than the normal upper limit.

How that’s defined depends on your child’s age and physical condition.

For example, tachycardia in newborns refers to a resting heart rate that may be faster than that of an older child. A teenager is considered to have tachycardia if their resting heart rate is higher than 100 beats per minute. Consult with your child's health care professional if you suspect your child’s heart rate is too fast.

Sinus tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia can be a normal increase in the heart rate if it is in response to exercise or physical or emotional stress. It’s common in children, and usually no treatment is needed.

Sinus tachycardia can also be caused by fever, increased thyroid activity or conditions such as anemia (low blood count), although rare. In these instances, the tachycardia usually goes away once the underlying condition has been treated.

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

Another common tachycardia in children is supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). It presents in two forms: paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (PAT).

When a child has SVT, electrical signals in the heart’s upper chambers (atria) travel abnormally in the heart. This interferes with electrical impulses coming from the sinoatrial (SA) node, the heart’s natural pacemaker. This disruption results in a faster than normal heart rate.

SVT in infants

SVT can occur in infants. It’s usually accompanied by a resting heart rate of more than 220 beats per minute. Infants with SVT may also breathe faster than normal, struggle to nurse or bottle feed, sweat heavily when feeding, seem fussy or appear sleepier than usual. With proper diagnosis and treatment, SVT can be a short-lived condition in infants. Symptoms often disappear within months.

In some cases, SVT can be detected while a baby is still in the womb. An expectant mother may be advised to take medications to slow down her baby’s heart rate.

SVT in children and teens

SVT doesn’t pose a life-threatening problem for most children and teens. Children with SVT usually have a heart rate of 180 to 220 beats per minute. Treatment is considered only when the child suffers shock or loses consciousness or if episodes are prolonged or frequent. School-age children and teens may be more likely to have SVT.

A child with SVT may be aware of their rapid heart rate, as well as other symptoms that include:

- Heart palpitations

- Dizziness

- Lightheadedness or fainting

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Fatigue

SVT doesn’t keep most children from enjoying normal activities. Medication may be needed to keep the tachycardia under control. Your child’s health care professional will also want to see them periodically for monitoring.

Some children can learn ways to slow down their heart rate, such as using the Valsalva maneuver – closing the nose and mouth and straining to breathe out or putting cold water on their face.

Treatment

Treating SVT usually includes focusing on stopping the current episode and preventing recurrences. Your child’s age also helps inform the treatment approach.

SVT treatment options for children include:

- Medications, including IV medications

- Ablation, using a thin, flexible tube inserted through the nostril

- Cardioversion, a small electrical shock to the chest wall

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW)

In this disorder, electrical pathways between the upper chambers (atria) and lower chambers (ventricles) of your child’s heart malfunction, allowing electrical signals to reach the ventricles to early.

Those electrical impulses can then be “bounced back” to the atria. This short-circuiting of electrical signals can produce overly fast heart rates.

Often medication can improve this condition. In rare cases when medication is not effective, other treatment options include delivering a shock to the heart (called cardioversion), catheter ablation and surgical procedures.

Ventricular tachycardia

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is a fast heart rate that starts in the lower chambers (ventricles) of your child’s heart.

This condition is uncommon but potentially very serious. In some cases, ventricular tachycardia can be life-threatening. It requires immediate medical attention.

Ventricular tachycardia may result from serious heart disease. It can occur in children with otherwise normal hearts or those with a congenital heart defect.

Specialized tests, including an electrophysiology study, may be needed to evaluate the tachycardia and the effectiveness of medications that treat it. Other possible treatment options include cardiac ablation and surgery to place an implantable cardiac defibrillator.

Some forms of ventricular tachycardia may not need treatment.

Bradycardia

Bradycardia is a slower-than-normal heart rate.

What’s considered too slow depends on a few factors, including your child’s age.

A newborn usually won’t have a heart rate under 80 beats a minute. An athletic teenager could have a normal resting heart rate as low as 50 beats a minute.

Sick sinus syndrome

When the sinus node doesn’t fire its electrical signals properly, the heart rate slows down, pauses or speeds up. This is called sick sinus syndrome. It can cause a heart rate that’s too slow (bradycardia) or too fast (tachycardia).

A child with sick sinus syndrome may be tired, dizzy or faint. Some don’t have symptoms.

Sick sinus syndrome can affect children with congenital heart disease, especially those who have had open-heart surgery with scarring in the right atrium.

For children with serious symptoms, an artificial pacemaker is often placed to increase their heart rate.

Complete heart block

Heart block occurs when the heart’s electrical signals can’t pass normally from the upper chambers of the heart to the lower chambers. Without electrical impulses from the sinus node, the ventricles can still contract and pump blood, but at a slower rate than usual.

Heart block can be caused by disease, injury to the heart during surgery, certain medications or a congenital defect.

Treating complete heart block may require an artificial pacemaker.

Checklist for parents of children with arrhythmias

Learn to check your child’s heart rate

You need to check your child’s heart rate to help monitor an abnormal heart rhythm.

You can do this by feeling for your child’s pulse or by listening to their heart with a stethoscope. Stethoscopes can be purchased online or at some drugstores. You’ll need a clock or watch with a second hand to count the number of beats in one minute. Your child’s health care professional can give you detailed instructions.

Learn to slow your child’s heart rate

If your child has recurring bouts of tachycardia (fast heart rate), your child’s health care professional may teach you and your child ways to slow the heart rate.

Sometimes coughing or gagging helps. Holding an ice pack against the face sometimes works as well. The Valsalva maneuver – closing the nose and mouth and straining to breathe out – can also work well.

Always follow your child’s health care team’s recommendations exactly. Don’t be afraid to ask questions if you don’t understand the instructions.

Understand and manage medications

Parents of a child taking medication for an abnormal heart rhythm should give their child their medications at the right time. Some arrhythmia medications must be given at regular intervals during the day.

Your child’s health care team will tell you how to give the medication with the least inconvenience to you and your child. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.

Always give medications exactly as recommended. Never stop medications without checking with your child’s health care professional first.

Learn CPR and emergency procedures

All parents should learn CPR. You could help save your child’s life, including in cases of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

CPR skills, including recognizing the signs of breathing problems and cardiac arrest, are vital if your child has heart disease or is at risk for life-threatening arrhythmias.

Understand and manage your child's implanted device

If your child has an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) or a pacemaker, your child's health care professional will give you information about the device and how to check it.

If your child has a pacemaker, a special device lets you use the phone to transmit a signal from the pacemaker to your child’s health care professional. This provides insight into your device’s day-to-day functioning. If there’s an issue, someone from the medical team will contact you and tell you what to do.

There are similar considerations for an ICD. Your child’s health care professional will want to check the device periodically to check its battery and overall effectiveness.

With either device, it’s important that you and your child both carry an ID card that alerts medical personnel about their implanted device. The presence of an ICD or a pacemaker in your child’s body might prohibit some medical procedures, including those that use strong electromagnetic fields.

Learn more:

- Devices that can interfere with ICDs or pacemakers

- Living with an ICD – print an ICD ID card (PDF)

- Living with a pacemaker – print a pacemaker ID card (PDF)

Know what to avoid

It’s important for you and your child to be aware of activities or medications that might cause an arrhythmia. Your child’s health care team should talk to you about what to avoid.