Low-level toxic metal exposure may raise the risk for clogged arteries

By American Heart Association News

Environmental exposure to low levels of toxic metals may raise the risk for developing clogged arteries, according to a study of auto workers in Spain.

The findings, published Thursday in the American Heart Association's journal Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology, found a link between low levels of cadmium, arsenic and titanium in the urine of workers at an auto assembly plant in Zaragoza, Spain, and a buildup of plaque in the arteries of their necks, hearts and legs.

"Metals are ubiquitous in the environment, and people are chronically exposed to low levels of metal," lead study investigator Maria Grau-Perez said in a news release. She is a biostatistician at the Institute for Biomedical Research Hospital Clinic de Valencia INCLIVA in Valencia, Spain, and a Ph.D. candidate in the department of preventive medicine, public health and microbiology at the Universidad Autonoma de Madrid.

"According to the World Health Organization, 31% of the cardiovascular disease burden in the world could be avoided if we could eliminate environmental pollutants," Grau-Perez said.

Previous research has shown a link between exposure to toxic metals found in drinking water, air, food and tobacco smoke and a higher risk for cardiovascular disease. There also is evidence that a reduction in exposure to metals such as lead and cadmium contributed to a 32% decline in cardiovascular mortality rates in the U.S.

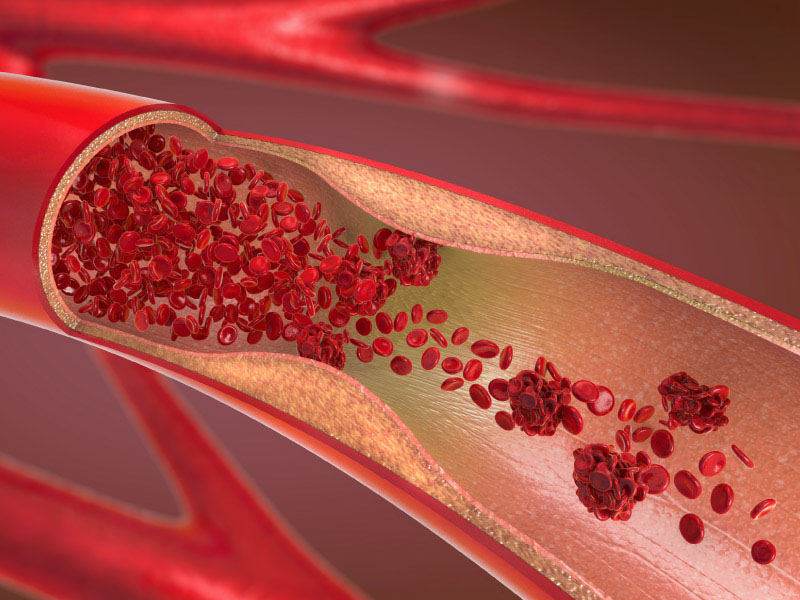

Investigators in the new study looked more closely at the association between the development of arterial plaque and environmental exposure to toxic metals. Atherosclerosis – a buildup of plaque in the arteries – is the main underlying cause of cardiovascular disease.

They analyzed levels of nine toxic metals found in the urine of 1,873 Spanish auto workers who were 40-55 years old. The metals included arsenic, barium, uranium, cadmium, chromium, antimony, titanium, vanadium and tungsten. They also looked at whether the auto workers had plaque in their neck, heart and leg arteries.

They found the likelihood of having clogged arteries was higher in auto workers whose urine contained arsenic and cadmium – metals often found in food and tobacco – and titanium, which is found in dental and orthopedic implants, pacemakers, cosmetics and auto manufacturing plants.

"This study supports that exposure to toxic metals in the environment, even at low levels of exposure, is toxic for cardiovascular health," study co-author Dr. Maria Tellez-Plaza said in the release. She is a senior scientist at the National Center for Epidemiology and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III in Madrid.

"The levels of metals in our study population were generally lower compared to other published studies. Metals, and in particular arsenic, cadmium, titanium and likely antimony, are relevant risk factors for atherosclerosis, even at the lowest exposure levels and among middle-aged working individuals."

Clogged arteries can lead to heart attacks, stroke, angina, peripheral artery disease and kidney disease. Investigators in this study were examining the earliest stages of plaque buildup, called subclinical atherosclerosis, which occur before any symptoms are present.

This study also included imaging of the femoral artery – the main artery supplying blood to the lower body – because research suggests plaque buildup there may occur during the early stages of cardiovascular disease.

The research showed plaque in the carotid arteries in the neck was more likely to appear in people whose urine contained cadmium and arsenic, whereas people with higher levels of cadmium and titanium showed more plaque buildup in the femoral arteries. Plaque in the coronary arteries was associated with titanium.

It also found older study participants had higher levels of toxic metals in their urine than younger ones; women had higher levels than men; and adults who had smoked at any point in their lives had higher levels of arsenic, cadmium, chromium and titanium than those who had never smoked.

The authors said their findings provide further evidence of the need to reduce exposures to toxic metals.

"Current global environmental, occupational and food safety standards for cadmium, arsenic and other metals may be insufficient to protect the population from metal-related adverse health effects," Tellez-Plaza said. "Metal exposure prevention and mitigation has the potential to substantially improve the way we prevent and treat cardiovascular disease."

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].