She's a heart doctor. Her son got COVID-19. Then she did. And her husband … and daughter.

By Nancy Brown, American Heart Association CEO

This is a cautionary tale. It's the story of someone who should've known better not taking the coronavirus seriously enough.

This is also a tale of discovery. It's the story of someone forced to find new ways of doing things and actually liking them.

Most of all, this is a raw tale. It's the unvarnished story of Dr. Stacey Rosen, a cardiologist/researcher/hospital executive, wife/mother/daughter and COVID-19 survivor.

***

Circumstances aside, Stacey savored a spontaneous weekend with her favorite people.

It was early March, when Americans were trying to understand the virus upending our world. The World Health Organization had yet to declare a pandemic.

Still, the coronavirus was worrisome enough to fill the suburban New York home of Stacey and her husband, Dr. Mark Silverman. Their 21-year-old daughter, Sarah, came home from college in Pennsylvania. Stacey and Mark insisted their 27-year-old son, Max, come home; he'd been working from home in his Upper East Side apartment while his wife was in Chicago working on her master's degree. Max's twin sister, Rebecca, and her boyfriend joined them.

Having everyone together prompted Stacey to let her guard down. The mood was so festive, the weather so delightful, that Stacey invited her 81-year-old mother for an outdoor lunch on Saturday.

Between bites of pizza and sips of wine, the group laughed about the wacky side of the headlines: a toilet paper shortage?! When Grandma headed home, Max gave her a kiss on the cheek goodbye.

On Monday morning, Max woke up with a fever, shakes and chills.

***

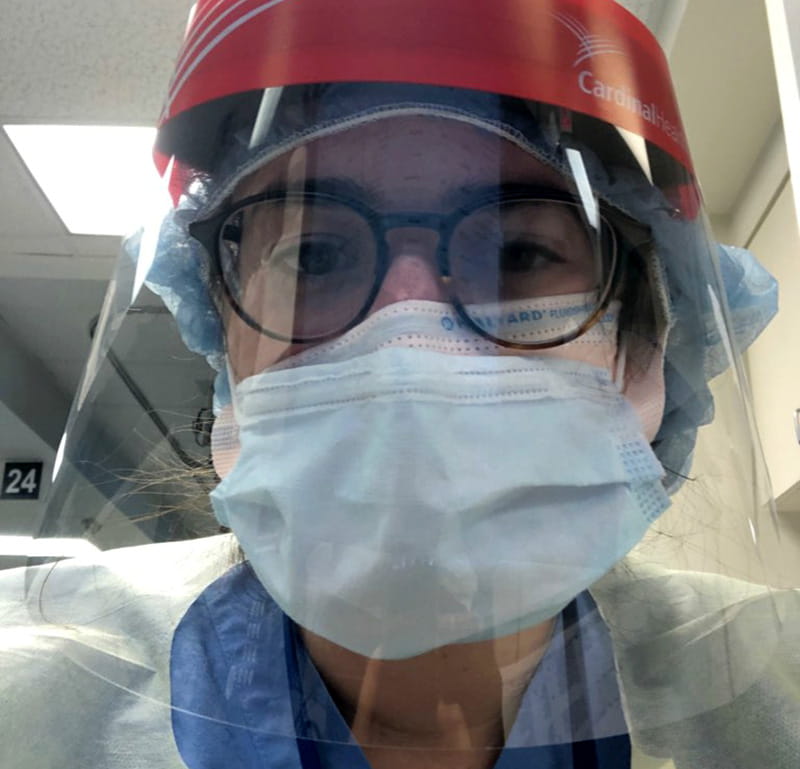

Stacey is the senior vice president for the Katz Institute for Women's Health at Northwell Health, New York's largest health care provider, and a practicing cardiologist. Her husband, Mark, is a dermatologist. Their daughter Rebecca is an intern at a Brooklyn hospital that would soon be an epicenter of COVID-19 cases. The night of their family dinner, Mark's sister – an infectious disease specialist – was working on the clinical trial that would lead to the drug remdesivir being recommended to treat COVID-19.

Stacey had a unique insight into the devastating powers of a new infectious disease. The formative days of her career were the formative days of HIV and AIDS. She had treated patients who'd never heard the terms. She had to explain how easily they could spread the virus. She also delivered the excruciating fact that, at the time, AIDS was practically a death sentence.

"It marked my approach to medicine forever," she said.

Fast forward to early March.

Stacey spent the week making sure everyone on her team had the tools and skills to work remotely. One of the toughest people to rein in was herself.

As someone who thrived on being surrounded by colleagues and patients, she didn't like working from home. She couldn't even decide where to set up her laptop.

***

Max's symptoms forced Mark to cancel his office hours. Stacey went into denial, insisting it was "ridiculous" to think Max had COVID-19; it had to be something else.

Max got tested anyway. When it came back positive, Rebecca screamed at Stacey: "You exposed Grandma to this!"

Max went into quarantine in the basement. Stacey delivered food on trays outside his door.

"We cleaned constantly," she said. "There were wipes everywhere."

Meanwhile, Stacey tried replicating her workweek as best as she could.

The awkwardness of working in sweats from her sofa alongside her kids left her off-kilter. She felt less engaged in meetings. She was more irritable. She thought it was the new setup that left her off-kilter.

By Thursday, she could hardly move. When she did, it hurt.

"I've only had influenza once," she said. "This felt like that on steroids."

She got tested Friday. Despite her training, her infected son and her symptoms, Stacey again clung to denial. Until the call came that she, too, tested positive.

***

Mark let Stacey have the master bedroom. But it was too late. COVID-19 blasted him Monday.

That made three positive cases. And each manifested differently.

- Max endured several days of fever and horrible headaches. He rebounded enough to become the primary caregiver to his parents.

- Mark was OK most days, albeit tired because of his awful nights: drenching sweats that required changing the sheets multiple times. That lasted about a month.

- Stacey felt pulverized by fatigue and muscle aches. She couldn't smell or taste anything for about five weeks; it took about eight weeks to regain the taste and smell of her morning coffee.

"We were all miserable," Stacey said. "I would try taking a shower and have to sit down on the floor of the shower because everything hurt."

Amazingly, Grandma remained healthy, as did Max's twin Rebecca, who faced added risk working in a hospital. Rebecca's boyfriend was OK, too.

Then there's Sarah, Stacey's youngest.

Of the four people living in the house, Sarah was the only one not bedridden by the virus.

"But when we all went to do antibody testing, she had the highest antibodies in our family," Stacey said.

So make it four cases, four manifestations.

***

As Stacey and her family improved, cases skyrocketed across the nation. The more it spread, the more varied – and scary – the outcomes.

Young, healthy people were having strokes and heart attacks. Organs were failing. Bodies were turning against themselves via cytokine storms. Death wasn't limited to those who were old and compromised.

Stacey shifted from denier to worrier. Every headache became a potential blood clot. She couldn't believe how cavalier she'd been. She also couldn't believe how lucky her family was.

"If I knew then what I know now, I would have been an insane mess," she said. "I'm so relieved and really grateful for how this played out for us."

***

While Stacey healed, her hospital scrambled.

Beds were in such high demand that an auditorium was converted into an ICU; chairs were unbolted from the ground to make way for gurneys and lifesaving equipment. Some administrators helped convert New York's Javits Convention Center into a temporary field hospital. Others worked with the Navy hospital ship brought in to provide more beds. Stacey could only imagine the stress her friends endured.

Some of her cardiology colleagues pitched in on critical care teams. Her recovery made it impossible to even consider joining them. She felt guilty.

Hearing that fewer people were calling 911 or arriving at the ER with chest pains (now the focus of the American Heart Association's "Don't Die of Doubt" campaign), she worried whether any of her patients made those mistakes.

It was a lot to think about.

***

Stacey had never had so much time to sit and think.

She grew up in a house where people got up early, got dressed and tackled their to-do lists. She's always had a lengthy one. Before her current job, she was chief of cardiology at another major hospital. She routinely worked 18-hour days when her kids were growing up.

Yet from mid-March through late June, she routinely ate dinner with her husband and at least two of their kids, then went for a long walk. They did quiet stay-at-home stuff that she'd never done and, frankly, always thought she'd hate. She loved it. Even when three of them were battling COVID-19, Stacey remembers feeling like "we were our own personal little army against the world."

"I have a new appreciation for the simple things in life," she said. "I was kind of sad when Max left. I got used to the new normal with me, my husband and two or three kids together every night. You know, a life that's a little bit slower than the one I lived for a couple of decades is really nice."

Soon, she found a professional parallel.

***

When Stacey said treating AIDS patients in the early 1980s "marked my approach to medicine forever," those lessons came in layers.

On the surface, it taught her to understand – fear, even – the persistent, destructive power of a strange new virus.

Deeper, it showed her the power of quiet moments spent counseling, consoling, connecting.

"I feel like I am in the most privileged profession," she said. "I get to be part of people's lives in the most intimate way. I'm 35 years out of med school and the aura and the responsibility and the privilege has never left me."

Actions back those words.

She's turned down several jobs that would've required her to stop treating patients. In every administrative role she's accepted, she's made it clear to her bosses that she will bail out of any meeting if a patient is having chest pain.

Her stance is based on more than pride.

"I think it gives a doctor credibility," she said.

So once Stacey regained the strength to carry on a conversation, she began seeing patients via telemedicine. Appointments felt like reunions. Away from the cacophony of the office, conversations had room to breathe. Updates on blood pressure and medications were followed by details about a child's wedding or the birth of a grandchild.

"I've been in the same health care system for 25 years and I have patients who I've cared for that whole time," she said. "It's kind of nice to reconnect with them and not worry about anything else. The sweetness of these conversations – it's really lovely, something special."

***

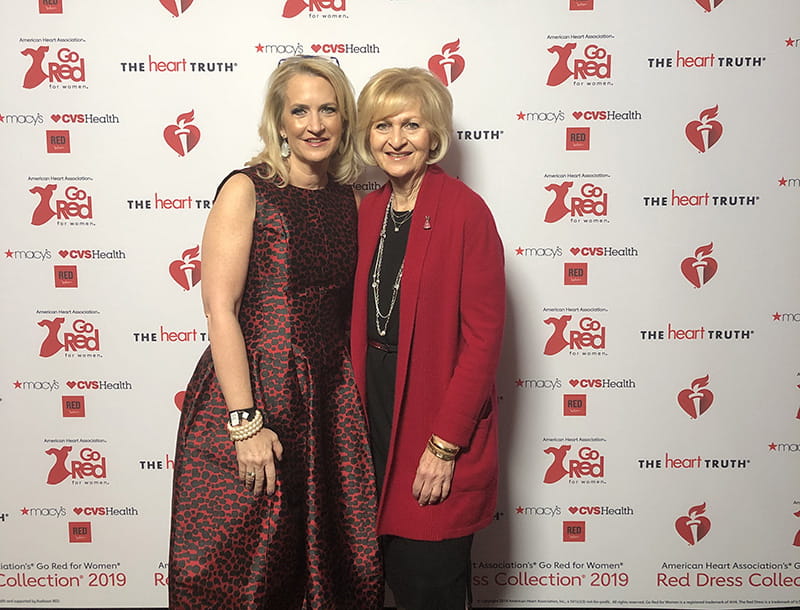

Throughout her career, Stacey also has been a devoted volunteer for my organization, the American Heart Association.

She's currently president of our Eastern States region, a relatively new organizational structure at the AHA that merged three regions into a new region covering the Northeastern Seaboard. This new grouping isn't as tough as making teammates of Yankees fans and Red Sox fans, but it does require some finessing. So she planned to visit each office. Of course, that was pre-pandemic.

Yet the plan wasn't scuttled. If anything, video meetings made it easier for her to spend more time with more people.

Stacey noted that many of our nation's flaws have been exposed by the coronavirus. But she's proud of the fact that the AHA is working to improve the societal risk factors that can harm the health of many Black and Hispanic people, including historical inequities and a lack of access to health care.

"I hope that we've learned lessons that are sustainable," she said. "I'm kind of optimistic that these combined tragedies can maybe make for a better world."

***

The past six months have affected each of us in profound ways. Stacey's story offers plenty on both ends of the spectrum.

While she's open about the mistakes she made early on, she suffered for it – though not the ultimate price nor anywhere close, which she's thankful for every day.

Then there's the doctor who liked to get up early, put on a nice dress and cram 48 hours of work into each day. She fondly remembers that person. It'd be a stretch to say she's left it all behind, but it's fair to say she's developed a new approach to her career.

"It's really clear to me again why I went into medicine," she said. (Related anecdote: Her first day back at the hospital, slipping into her white lab coat made her feel "born again.")

She laughs at the fact it took a public health crisis to topple many notions she once held sacred.

"You know the expression 'never waste a good crisis?'" she said. "For me, the big takeaway is not to be afraid of change. There is something kind of exciting and invigorating about an environment where everyone is forced to change. We all start seeing things a little bit differently."

A version of this story appeared on Thrive Global.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].