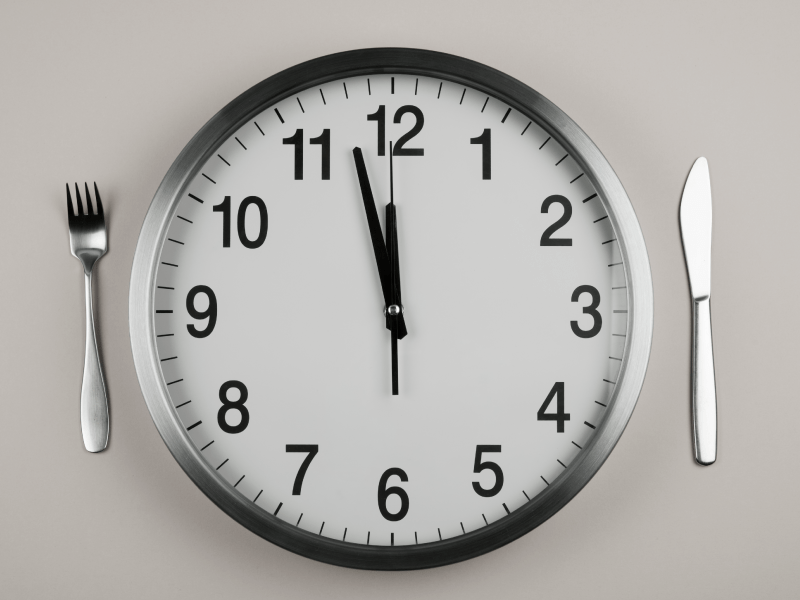

Time-restricted eating is growing in popularity, but is it healthy?

By American Heart Association News

Tipping the scales at 233 pounds, Charles Joy realized he needed to make some changes.

The 28-year-old Louisville, Kentucky, native already had tried many diet plans to varying degrees of success. In 2013, he lost more than 100 pounds through exercise and diet. But afterward, his weight slowly began to creep back up.

In 2017, Joy decided to try time-restricted eating, consuming all his meals within an eight-to 10-hour window each day. The pounds melted away. Today, he weighs 183 pounds.

"It's working much better, because it's so flexible," Joy said. "With calorie restriction, you have to plan out everything, and I was never satisfied. Now I don't even think about food until the afternoon."

Time-restricted eating is one variation of a hot diet trend that also includes intermittent fasting. According to Krista Varady, an associate professor of nutrition at the University of Illinois at Chicago, there are several types of intermittent fasting, including one meal per day, the 5/2 method, which involves five feast days and two days with restricted calories, and alternate-day fasting.

Fasting is nothing new. For a month every year, practicing Muslims celebrate Ramadan by fasting from sunrise to sunset, and it's a part of many other major religious traditions. But is it healthy and effective to restrict eating or fast on a regular basis?

It can be, said Varady, who said she has run more than a dozen clinical trials on alternate-day fasting and one on time-restricted eating.

In a 2017 JAMA Internal Medicine trial, Varady and her colleagues showed alternate-day fasting was just as effective as daily calorie restriction for losing weight and maintaining the loss.

"With alternate-day fasting, people typically lose 3 to 8 percent of their body weight over three to 12 months," Varady said. And it can work with both low- and high-fat diets.

Weight loss is not the only benefit. In a 2009 study, most of the study participants also saw reductions in the so-called "bad" LDL cholesterol and in blood pressure. Other studies show decreases in insulin resistance, which is associated with an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes. And diabetes is a risk factor for heart disease.

Alternate-day fasting works, at least in part, because people wind up consuming less food overall.

But those who use time-restricted eating can lose weight without restricting caloric intake, said Dr. Satchidananda Panda, a professor and researcher at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California. He also wrote a book about time-restricted eating.

"The science and the benefits of time-restricted eating are very different from those of other forms of fasting," Panda said.

According to Panda, time-restricted eating is based on the science of circadian rhythms, which control every hormone.

In a 2012 study, Panda and his team split mice into two groups. One ate all the sugary, fatty foods they wanted during a 24-hour period. The other group had the same sorts of foods but were only allowed to eat during an eight-hour daily window. Both groups consumed the same number of calories, but the mice that ate round-the-clock became fat and sick while those on a time-restricted diet did not.

Panda also has shown that fruit flies placed on a time-restricted eating plan have hearts that appear to be 20 to 30 percent younger than their age would suggest. Fruit fly hearts and human hearts are similar, so Panda believes it's reasonable to conclude humans might benefit in the same way.

"It works by slightly reducing ATP producing proteins of mitochondria in the heart and keeping the mitochondria healthy, which reduces oxidative stress," Panda said, noting that time-restricted eating gives the body time to repair itself. "Most of our studies are showing that the effect is on multiple organs and on the central nervous system. It's a positive feedback loop."

Panda hopes to continue his research, and find out whether the health benefits seen in animal studies hold true for humans. Data collected from his smartphone app, myCircadianClock, could be key. The app helps people track when they eat, sleep, exercise and take supplements and medications.

"We send them push notifications asking them what improvement they are seeing," Panda said.

In most of Panda's studies, people eat their first meal between 8 a.m. and 10 a.m. but Charles Joy typically waits until 4 p.m. to break his fast. Joy's doctor initially was concerned by the diet, but Joy felt vindicated by his low cholesterol and blood pressure readings. He has no plans to change things up anytime soon.

"I've been obese and super-unhealthy pretty much my entire life, the biggest guy in school," Joy said. "This feels great, and I want to keep it going as long as I can."

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].