Smoking in America: Why more Americans are kicking the habit

By American Heart Association News

More and more Americans are putting out their cigarettes — for good.

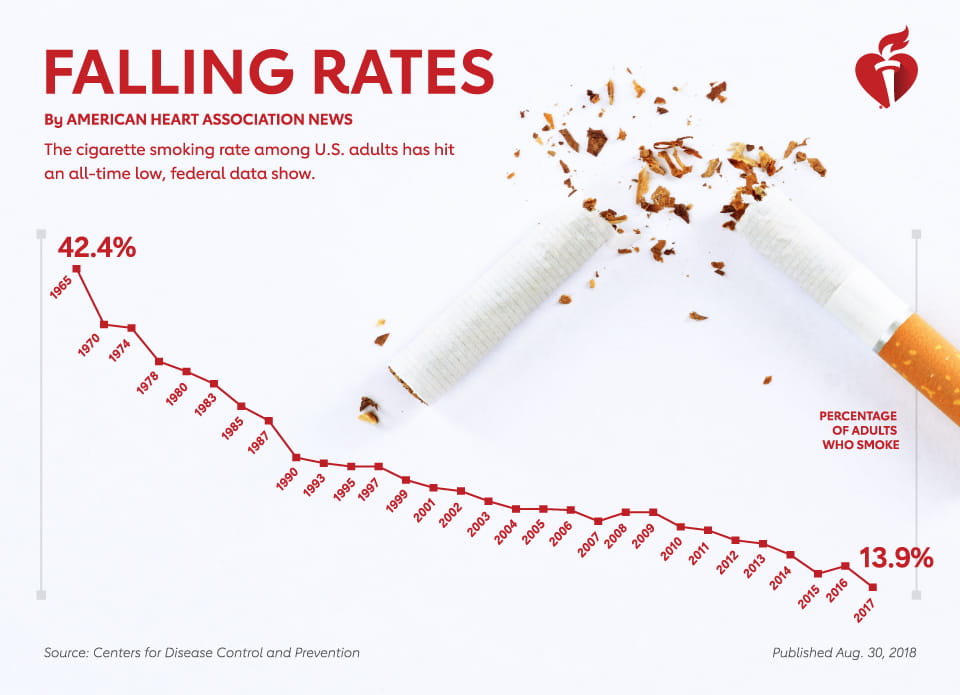

The overall cigarette smoking rate among U.S. adults has hit an all-time low, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preliminary data from the National Health Interview Survey showed that smoking rates declined from 15.5 percent in 2016 to 13.9 percent in 2017.

“Cigarette smoking among adults has been on a downward trajectory for decades,” said Brian King, deputy director for research translation in the CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health. “It’s the lowest percentage we’ve seen since we started monitoring smoking rates in 1965.” Still, the preliminary 2017 data indicates 34 million Americans still smoke, according to King. And an estimated 480,000 Americans die each year due to cigarette smoking and secondhand smoke exposure, according to the latest CDC data.

Fifty years ago, it seemed impossible to imagine a world where less than 15 percent of adults smoked. At the time, roughly 42 percent of American adults lit up, and smoking was a normal part of everyday life. You could smoke at work, in restaurants and bars, and on planes. You could buy cigarettes from vending machines. Tobacco was glamorously portrayed in the movies and on TV and advertised on billboards lining the highways.

That started to change in 1964 when the surgeon general released the first report on smoking and health. The landmark report concluded that smoking causes lung and laryngeal cancer and is a major cause of health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, ushering in policies that would change the tobacco landscape.

But the decline in smoking rates didn’t happen overnight. It took time for anti-smoking campaigns and policies to unfold, said Dr. Charlie Shaeffer, a California-based cardiologist who has been active in tobacco control efforts. And quitting the highly addictive products required tools and resources that didn’t yet exist.

Both King and Shaeffer credit the combination of cigarette price increases, anti-smoking campaigns, smoke-free laws, and access to cessation programs as powerful levers aided by health advocacy groups. “These interventions really de-normalize tobacco use,” said King.

Higher-priced cigarettes made it more expensive to smoke, especially for teenagers — an age when most smokers first tried smoking. Money raised from taxes funded ads that showed the adverse health impacts of tobacco, sometimes in gruesome detail. And not being able to smoke at work, bars or public places created smoke-free environments, making it easier for people to not smoke. Plus, in 2010, most commercial health insurance plans and Medicaid were required to cover smoking cessation programs, giving smokers access to the resources and tools they needed to quit.

But real strides in decreasing smoking have come from prevention efforts. Greater education, particularly aimed at children, spread the word about tobacco’s effects, and health warnings on products, beginning in 1965, reiterated that message. “We’re not getting an influx of new smokers on the front end. We’re starting to see the impact of reducing [smoking] initiation among youth and young people in overall smoking rates,” said King.

Text version of infographic(link opens in new window)

Text version of infographic(link opens in new window)

While lower smoking rates are a major public health success, experts say there’s still work to do.

“The numbers have declined but seem to be plateauing,” said Shaeffer. Among current smokers, the vast majority smoke daily. While they are smoking less, even just one cigarette a day increases the risk of heart disease and stroke, according to a January 2018 review published in the British Medical Journal(link opens in new window).

Plus, the tobacco environment is diversifying thanks to the emergence of products such as e-cigarettes, the health effects of which researchers are still working to understand as their popularity among young people grows. According to the CDC, 11.7 percent of high schoolers in 2016 said they had used an e-cigarette, up from 1.5 percent in 2011. Newer approaches will be needed to prevent tobacco use and nicotine addiction in a new generation, experts say.

“There’s an emerging body of novel interventions and strategies, such as increasing the age of sale of tobacco to 21, including e-cigarettes, and prohibiting the sale of flavored tobacco, which are percolating at the local level,” King said.

But he is optimistic that smoking rates will continue their downward trend.

“Ultimately, it’s going to take a coordinated effort at the national, state and local level,” he said. “We’re on track to meet the federal objective of a 12 percent smoking rate by 2020.”

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].