Meet the new AHA president: Mitch Elkind, the second neurologist to hold top post

It's 1991 and Mitch Elkind is at the point in medical school where he needs to pick a specialty. Although he's been headed to neurology all his life, he feels a tug toward cardiology.

Sitting in his apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he tells his girlfriend about fascinating heart procedures he could do. He raves about research opportunities.

"It's so obvious where you're headed," she says, laughing.

He's confused.

So she points to the book in his lap. The one he's been stroking throughout the conversation. The 1,600-page textbook, "Principles of Neurology."

Elkind indeed went into neurology and, as it turns out, got the same reward of fascinating procedures and landmark research projects, only these involved strokes.

He's also accomplished something else that might've seemed more attainable had he gone into cardiology: On July 1, he became the 84th president of the American Heart Association; he's only the second neurologist to serve as the volunteer leader.

When Elkind was named president-elect last year, the move fit the AHA's planned expansion of work in brain health. Then came the coronavirus, shifting priorities. Yet Elkind remains a great choice because of another part of his biography: He's spent the last 20 years studying how infections can be a cause of stroke.

Well-timed twists and turns are a hallmark of Elkind's career. No wonder AHA CEO Nancy Brown described Elkind as "the right person at the right time."

***

Growing up in the New York City suburb of New Rochelle, Elkind's childhood revolved around headaches.

Treating them, that is.

That was his dad's specialty. And his mom handled everything else about the practice.

Arthur Elkind never set out to study headaches. In the 1950s, he got a fellowship in kidney disease and worked for the headache center at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx. The first such center in the world, it was led by founder Dr. Arnold Friedman.

Another upstart doctor on the team was Oliver Sacks; this was long before he became a professor at NYU and a best-selling author about unusual neurology cases.

When Friedman died, Arthur served for several years as acting director of the Montefiore Headache Center. Then he launched the Elkind Headache Center, treating patients and running clinical trials.

In retrospect, Arthur stretching from his training in nephrology to the realm of neurology set an example for Mitch. So did Arthur's devotion to the larger community of headache sufferers. He spent many years as president and board member for the National Headache Foundation and held various roles in domestic and international headache societies.

Despite all his exposure to science, it didn't interest teen Mitch.

"I was interested in the philosophy of the mind, and thought maybe I would become a writer," Elkind said. "I wanted to understand how the mind works, the mind-brain duality, how physical matter can lead to conscious thought and create human activity."

Notice that baby step toward neurology? Here's a more direct link: He read a lot of books by Sacks.

Then Mitch joined his dad at a National Headache Society gala.

"The guest speaker was Oliver Sacks and he sat at our table," Mitch said. "Having the opportunity to talk to him over dinner was a highlight of my early career."

***

As Elkind finished college, he got into Harvard Medical School. He also received a fellowship to pursue a Ph.D. in history and philosophy of science at Cambridge University.

Off to England he went.

He earned a master's degree in a year. Then, "like a musician who realizes they love music too much to make it their profession," he decided it was time for medical school.

He returned to Harvard wired for neurology but open to anything. That's how cardiology worked into that fateful conversation with Rachel Vail, a friend since elementary school who'd become his girlfriend.

They married in 1993, not long after she helped steer him to neurology and shortly before he started his career at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Elkind planned to specialize in epilepsy. The wannabe writer with a master's in philosophy and a bookshelf full of Sacks would pursue questions such as: "Did some of the great artists have seizure disorders that led to their great insights? Was epilepsy why Van Gogh created his passionate colors and why Dostoevsky wrote so much?"

But Elkind found himself working for some of the giants in stroke care: Dr. C. Miller Fisher, whose career highlights include identifying transient ischemic attacks as a precursor to a stroke, and Dr. Walter Koroshetz, then the neurology residency program director and now director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Strokes at the National Institutes of Health.

Elkind also realized he was working at one of the leading stroke hospitals just as breakthrough after breakthrough made possible effective treatment of stroke.

Put it this way: When Elkind arrived for his residency, detailed stroke diagnoses came from observations; verification could only come from autopsy and little could be done to treat them anyway. By the end of his residency, MRIs offered a real-time view into the brain, a medicine could dissolve the clot causing a stroke and, in other cases, an invasive procedure could remove brain clots.

***

After 12 years in Boston, Elkind headed back to New York for a fellowship at Columbia University Medical Center. He expected to train under Dr. Jay P. Mohr, the stroke program director who'd also trained under Fisher.

"I'd love to have you, but I don't have a spot," Mohr told Elkind. "You should talk to the guy down the hall."

So Elkind walked into the office of Dr. Ralph Sacco.

That meeting sent Elkind's career down a new path.

Under Fisher and Koroshetz, Elkind had learned how to solve the puzzle of an individual stroke patient. Sacco's specialty was puzzles involving thousands of stroke patients. Elkind began delving into the underexplored areas of whether inflammation and infection cause strokes, earning a master's degree in epidemiology. He began building his career at the intersection of neurology and epidemiology.

Sacco left Columbia in 2007. In 2010, he became the first neurologist to serve as president of the American Heart Association.

***

Elkind describes himself as a "thinker," someone who ponders things from all angles before doing.

Once he does, though, he goes all in.

The combination has left him juggling many roles and leading many research projects. These are the potential game changers:

- The Northern Manhattan Study

Around the same time Elkind started at Mass General, Sacco launched the Northern Manhattan Study to figure out what caused strokes in Hispanics.

It's grown into the first large epidemiological study of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and brain health in Hispanic, Black and white people. The project includes over 4,000 enrollees.

"We've moved from talking about stroke risk to looking at the risk of cognitive decline and dementia as well," said Elkind, who is now co-director of the Northern Manhattan Study with Sacco.

- The ARCADIA trial

Launched in 2017 by Elkind and colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine and the University of Washington – and formally called the AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke trial – this project looks into the connection between atrial diseases (other than atrial fibrillation) and stroke.

Their hypothesis: AFib is a common manifestation of atrial disease and it's known to cause strokes. But what if it's not the AFib itself that causes strokes? What if AFib is a marker of an underlying, stroke-causing atrial disease? If so, someone without AFib – but with the underlying atrial problem – could be at higher risk of stroke.

"I believe there are a lot of people who have this underlying condition who haven't yet had atrial fibrillation," he said. "If we can find these markers for atrial cardiomyopathy, then we'll know who is at an increased risk and we can treat them without waiting for AFib to manifest. If we turn out to be right, we establish this entity of atrial cardiomyopathy as a disease entity that should be considered and treated, classified and categorized."

The ARCADIA trial, which is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, with additional support from the BMS-Pfizer Alliance for Eliquis and Roche, includes patients at approximately 150 sites – and growing.

- Link between infection and stroke

Since the dawn of stroke research, some people have thought infection could be a cause. Not many, though, and their voices were drowned by all the talk of known risk factors such as diabetes, cholesterol, obesity and smoking.

"So the idea that infection would lead to stroke was considered a little bit heretical," Elkind said.

Maybe that's what drew him to it.

For the past 20 years, he's studied whether flu or sepsis or other bacterial infections can change the body, making them more likely to have a stroke. This remained a fringe belief – until COVID-19 patients began suffering strokes at a higher rate than the general population.

"It feels like a little bit of a vindication," Elkind said. "Of course, I wish that it didn't have to happen as a result of a global pandemic."

***

When Elkind was a resident, he began attending the AHA's annual International Stroke Conference, back when it was a small, intimate gathering conducted within a single hotel ballroom.

A few years later, he sought funding of his own research for the first time. He got it from the AHA, receiving the first Kathleen Scott Research Fellowship grant. (He used it to study whether inflammation can lead to strokes. "It does," he said.)

That grant sealed Elkind's commitment to the AHA.

He began attending local meetings. He joined the New York City board of directors. Then came a spot on the regional board. Then three terms on the national board. And two terms as chair of the American Stroke Association Advisory Committee. (The American Stroke Association is a division of the AHA.)

During his years on the national board, Elkind got to know fellow board member Bert Scott. It was Scott's donation in memory of his late wife, Kathleen, that created the grant that kickstarted Elkind's career and his devotion to the AHA. Last year – while Elkind watched Bob Harrington's presidency – Scott began a two-year term as chairman of the board. Thus, Elkind and Scott are the president-board chair tandem this year.

As nice as that timing is, the more practical timing is the fact that the scientist expected to push the AHA more into brain health is also quite capable of pushing the AHA more into the fight against an infectious disease that triggers heart disease and stroke.

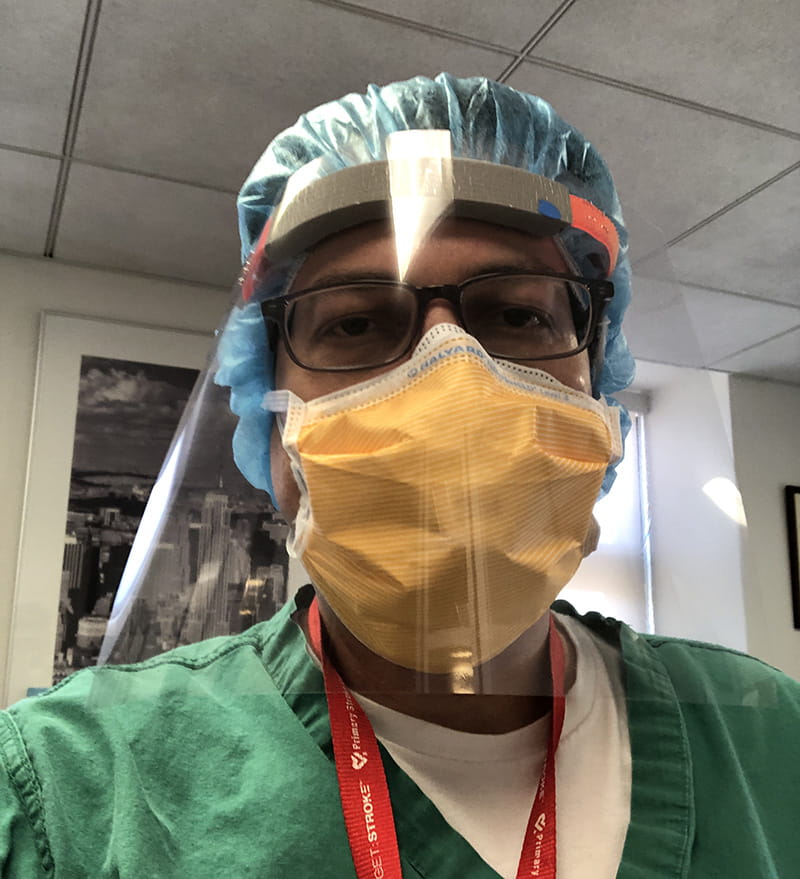

Elkind rang alarm bells about the coronavirus at a February board meeting. In March, weeks before the outbreak was deemed a pandemic, he awoke in the middle of the night and wrote the rough draft of what became an article in the journal Circulation outlining the AHA's role in the fight against COVID-19. In April, when the AHA launched a nationwide registry to track cardiovascular data of COVID-19 patients, he joined the steering committee.

"I hope to show that the AHA is capable of responding to a once-in-a-century public health crisis with leadership, commitment, science and passion in a way that few, if any, other organizations are capable of doing," Elkind said.

***

At 55, Elkind enjoys a well-rounded life beyond work.

His wife, Rachel, is an award-winning author of books for kids, tweens and teens. Their older son, Zachary, is a theater director and English teacher in Brooklyn. Their younger son, Liam, is going into his senior year at Yale. At the start of the pandemic, he and a friend started Invisible Hands Deliver, which connected young, healthy people to bring necessities to vulnerable people who must stay home during the crisis. As it grew to 12,000 volunteers, Liam was interviewed by most major TV networks and many publications.

"Liam came up with a creative solution to a tragic situation, and what he started in New York has begun to expand to other cities. He has essentially started a vital nonprofit organization in the midst of a pandemic," the proud dad said. "It's been a great learning experience for him."

Whenever they can, the Elkind family – including a Russian tortoise named Lightning, whose breed makes him more like a slow-moving dog than a tank-dweller – escapes Manhattan to a home in Connecticut. In summers, they paddle on a nearby lake, hike and run. In winters, they go cross-country skiing. Regardless of the weather, they cook great meals together, bake bread, and discuss politics, theater and philosophy.

In New York City, they happen to live on the same street philosopher John Dewey lived on when he taught at Columbia from 1904-1930. During college, Elkind liked Dewey so much that he framed his college thesis around what he imagined would be Dewey's approach to medical ethics.

"In his time, there was a big debate in the education community about learning versus doing," Elkind said. "He said it's not one or the other – you really need both. It sounds pretty obvious, but at the time he had a huge influence on education."

There's a parallel to be drawn between Dewey's point and Elkind's term as AHA president.

In a year that will be defined by COVID-19, the organization needs both a learner and a doer. Maybe even a writer-turned-philosopher-turned-neurologist-plus-epidemiologist who studies the connection between stroke and infectious diseases.