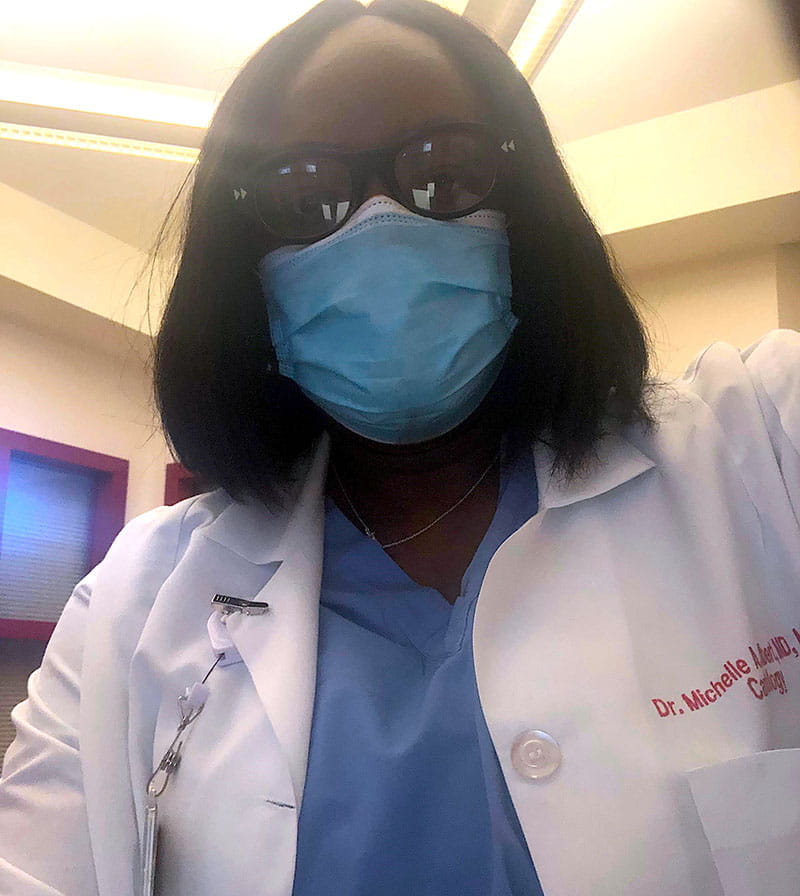

New AHA president Michelle Albert's lived experiences make her the right person in the right place at the right time

Dr. Michelle A. Albert is one of those people who seemingly does it all.

As the founding director of the NURTURE Center, she seeks innovative ways to curb heart disease and other health problems that stem from adversity, particularly among women and people from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

As a researcher, she leads studies about the physical, social and economic challenges facing people struggling with their weight, and the impact of COVID-19 on the cardiovascular health of Black women.

As a cardiologist, she sees critically ill patients, many of whom may not otherwise see a heart doctor who looks like them and can relate to them.

As a medical school dean of admissions, she's helping create a more diverse workforce of doctors.

As a mentor, she's highly sought by trainees, faculty and practicing doctors.

Then there's her leadership.

She's involved at the highest levels of several federal agencies. She just finished overlapping terms as president of two organizations. And, on July 1, she began perhaps her most prominent role yet: president of the American Heart Association.

"It's another way to make a difference," said Albert, the 86th person to serve as the AHA's top science volunteer, and the first Black woman to hold the job. "This is an excellent time to create meaningful change across barriers that are visible and invisible."

While Albert's many achievements clearly paved her path to this role, what makes her so perfectly suited to thrive in it now is something more valuable – her lived experiences.

At a time when the AHA is advancing cardiovascular health for all, including identifying and removing barriers to health care access and quality, Albert can relate to many of those barriers.

Because of what happened to her grandfather, she knows what happens when people get caught in a spiral that begins with a lack of resources and accelerates with a lack of access to quality care.

She understands fearing everything from physical safety to the emotional insecurity of being treated as "less than" because she's faced those fears herself.

She can empathize with anyone who believes they must build an impeccable resumé simply to be considered adequate by others. She also knows all too well the sensation of feeling like an outsider.

"Michelle is a brilliant scientist who is truly devoted to improving and extending lives for all people," AHA CEO Nancy Brown said. "Her relentless drive, her empathy and her determination to improve health disparities caused by historical and systemic problems – those are the characteristics forged on her unique journey that shine the brightest."

This is the story behind it all, both personally and professionally.

And it begins in Georgetown, Guyana, the capital city of a South American country that gained its independence from Britain only a few years before she was born.

***

Charles Albert was a dockworker. His wife, Caroline, worked as a seamstress. Like everyone they knew, the Alberts lived a meager life in a developing country.

This meant enduring long lines for food and gas. Wet newspaper sometimes sufficed as toilet paper. Televisions were rare; Guyana didn't get its first television station until Michelle was in college.

Charles and Caroline had two children: Volda, who became a social worker, and Michael, who was such a math whiz that the government sent him to pursue actuarial studies at the London School of Economics.

Michael and his wife, Carmen, left their 2-year-old, Michelle, and an infant, Maxine, to be raised by his parents, whom the girls called Grandfather and Granny.

"Everyone says I'm very serious," Michelle said. "It stems from them."

***

Michelle grew up so eager to learn that she dreamed about it. Often.

Many nights in her childhood and teenage years, she envisioned herself approaching a tree with a rough, thick trunk. A door magically slid up. She stepped inside and the door closed. When it opened again, she'd step into a lush place where everyone gathered to study.

"I remember feeling complete awe," she said. "The environment offered so many possibilities."

Michelle went to school by day, then spent her afternoons taking additional lessons. Grandfather walked her to all of it, usually wearing torn sandals that slapped against the soles of his feet.

Guyana followed the British education system. So when Michelle finished primary school, she tested for secondary school. She earned a spot at one of the top institutions, Bishops' High School.

The students were the children of the president and the minister of finance, as well as others born into wealth and privilege. This included the girl who became Michelle's best friend. Her affluent family gave Michelle rides to and from school as well as exposure to sports.

"That definitely shaped me," she said. "It made me industrious and focused."

***

As much as Michelle liked and excelled at math and science, her favorite subject was history.

She loved reading stories about the past because they gave her insight into the present. She found herself drawn to tales about the roughly 3 million Africans brought to Guyana by the British between the mid-1600s and the early 1800s as slaves.

"It was important learning for me because I knew I was living the ramifications," she said. "I realized how deep the roots were for the way we lived."

Michelle could connect the dots between herself and them in only a few strokes.

Granny's grandmother was believed to have been enslaved. That meant Michelle's great-grandmother, a woman she met several times and whose funeral she attended, was among the first generation in the family born free.

***

Grandfather retired when Michelle was 8. He remained active most days, until a stretch where he did a lot more sitting around. Granny also noticed that his legs were swollen.

One day when Michelle was 13, he announced that he was headed out for groceries. It seemed like a sign that he was feeling better.

The next thing Michelle remembers, a neighbor came running in with the news: Grandfather was dead. About 10 blocks away, his heart stopped. There was no CPR or defibrillation.

"It wasn't until I was in medical school that I realized he'd probably been in heart failure," she said. "If only we'd had more information then."

***

When Michelle was 9, her parents returned to live in Guyana.

Several years later, once they'd fulfilled obligations to the government, Michael and Carmen took the next step in a grand plan to better their family.

The couple moved to Brooklyn, securing jobs (Carmen had a master's degree in economics) and setting up a home. The final step was bringing Michelle and her sister. That happened a few months after Grandfather died. Both girls, along with Granny, moved to the East Flatbush neighborhood.

Back in Guyana, a quirk of Michelle's childhood was that she lived about a mile from a zoo. Many mornings, a lion's roar awoke her. Now, in her new home, a different sound rang out: gunfire. Drive-by shootings were common; on her first day of school, cops stormed onto campus to arrest classmates for carrying guns.

"Guyana and Brooklyn had the same desperation," she said. "In both places, I saw people with little who were just trying to make it."

***

Michelle was so advanced in her studies that she enrolled as a senior in high school despite being only 15.

She attended Erasmus Hall, a school with a proud history but a bleak present. More importantly, it was part of the Bridge to Medicine program, which allowed talented students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to take advanced science classes and college prep classes at the main campus of City College of New York.

The program was a game-changer for her. And, as with her experience at Bishops' High, some of her most indelible lessons came outside the classroom.

First off, there was the daily commute, a two-hour train ride each day. Stop by stop, she went from a gritty Black neighborhood to the "chichi" crowd of Park Slope to the business types swarming Wall Street to people of every background in midtown, then a Latino area in upper Manhattan.

"It opened a whole new world to me," she said. In time, she could look up from whatever she was working on and know where the train was merely by observing who was getting on and off.

Another perk of the program was getting to travel outside the city. A trip to Washington, D.C., marked the first time she stayed in a hotel. Then there were the college campus visits.

On a bus ride to the area outside Philadelphia that includes the liberal arts schools Bryn Mawr and Haverford, Michelle looked out the window and could hardly believe her eyes. This was the spectacular educational environment she'd dreamed about when she was inside the magical tree and the door lifted.

Suddenly, everything that seemed impossible now seemed possible.

She chose Haverford, a Quaker liberal arts college, in part because of how much the school revolved around its Honor Code. (To this day, students set and police all rules; exams are given without anyone monitoring them.) Alas, Michelle encountered a freshman-year housemate who didn't uphold high moral standards.

The housemate accused Michelle of stealing food, even though one of their other roommates was to blame. To Michelle, it was a harsh reminder of the fact that, for the first time, she was living "in an environment where people didn't all look like me." A saving grace was that it led her to find solace in the Black Students' League.

***

A full academic scholarship was a core reason she went to the University of Rochester Medical School. She also was attracted by an approach to medicine that was a bit ahead of its time.

Called the biopsychosocial model, it looked at how each of those disciplines – biology, psychology and socioeconomics – impacts health and disease.

Between being one of three Black students in a class of 110, and living in upstate New York, Michelle felt isolated. Yearning to get back to the big city, she was fortunate to land an internal medicine residency at Columbia University Medical Center.

During her third year, she became a chief medical resident. She also began eyeing cardiology fellowships. Johns Hopkins topped her list.

Then she heard Dr. Paul Ridker of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital speak about what would become his landmark work. It involves using molecules in the context of population health, a concept she didn't even know existed. Having majored in chemistry at Haverford, Michelle yearned for a way to incorporate that knowledge into public health.

"What he's doing is what I want to do," she thought.

As soon as Ridker finished, Michelle introduced herself. By the end of their conversation, Ridker said, "You should come to the Brigham. I could mentor you in my lab."

***

Ridker empowered her from the start.

As she went from cardiology fellowship to Harvard Medical School faculty member, Ridker named her science director of a large clinical trial. He chose her to be the lead author of a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Michelle expanded her interest in the intersection of molecules and race-socioeconomic status to more avenues involving under-resourced communities.

Today, that area is known as "social determinants of health," which are the conditions where someone is born and lives. She was studying it long before that phrase was commonly used. So was Dr. David Williams, a scientist of social and behavioral health at Harvard School of Public Health. His mentorship steered Michelle to her first major independent research funding.

"At that time, people in medicine knew things like race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status mattered to health outcomes, but they didn't traditionally consider those things very important," she said. "It wasn't seen as 'serious science.'"

So even though she was now inside the world of research, she still felt like an outsider.

"I knew people were always going to question me and my qualifications, so I wanted to create, as best as I could, a solid background," she said. "I had to be classically trained."

She earned a master's in public health from Harvard, then went through the Brigham Leadership Program, seven months of executive training done in conjunction with Harvard Business School.

***

After nearly 15 years at Harvard, Michelle was ready for a change. She became chief of cardiology at Howard University in 2012.

She enjoyed the atmosphere of a historically Black college. She especially enjoyed living in Washington, D.C., because her parents happened to have settled there, too. The timing was meaningful because her father was battling a form of bone marrow failure called aplastic anemia.

Michael died in 2014. The next year, Michelle was on the move again.

The University of California San Francisco offered her a place to start studying the biology of adversity. She became the founding director of the Center for the Study of Adversity and Cardiovascular Disease, which goes by the name NURTURE Center.

Under her guidance, researchers study how adversity affects social, behavioral and physiologic factors across the lifespan, with the aim of turning those insights into therapies and treatments for cardiovascular disease and more. The center's mission includes teaching and mentoring people interested in this field.

A few years ago, she also became the admissions dean for the UCSF School of Medicine. It's a unique role for a cardiologist, particularly one who is still practicing.

"We need a deep pipeline to diversify the workforce," she said. "I see medical school as mid-pipeline."

***

Through it all, Michelle has continued to stretch her expertise across the scientific community.

Her research accomplishments led to her election into the prestigious National Academy of Medicine and the American Society of Clinical Investigation.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently named her to the advisory board for its director. She's a member of the Board of External Experts for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

She served for the past two years as president of the Association of Black Cardiologists, Inc. For the last year, she also was president of the Association of University Cardiologists.

And, of course, she remained a steadfast AHA volunteer.

***

Over the years, Michelle held many roles at all levels of the organization, from being president of her local board to serving on multiple national committees. In 2016, she received the AHA's Women in Cardiology Mentoring Award.

In 2018, she flew to a hotel at the Dallas-Fort Worth airport to make a presentation for the AHA's Merit Award, a $1 million, five-year commitment for a visionary project.

She happened to be the final presenter. Just before she entered the room, the weary judges agreed that two candidates stood above the others. Dr. John Warner – then the AHA president and thus the leader of the panel – even acknowledged out loud that it was going to be hard to change their mind.

Michelle proposed a clinical trial focused on weight wellness and the social determinants of health. Participants would come from the San Francisco YMCA. While healthier weights and cardiovascular wellness would be the endpoints, they'd also learn about economics, job readiness and legal services.

Her idea was so compelling that the judges immediately reshuffled their rankings. Michelle became the first woman, and the first Black woman, to win the award.

In 2020, the AHA responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by creating Rapid Response Grants. Michelle was chosen to lead a study at UCSF and Boston University focused on how the new virus impacts Black women. Months later, she received the Population Research Prize, another award chosen by a panel headed by the AHA president, who was then Dr. Mitch Elkind, himself a population researcher.

"She's an inspiring person and a sophisticated thinker about how to address what's missing for a lot of people," said Warner, who remains on the AHA's board of directors. "She's an academic powerhouse. Every time I see her, I'm more and more impressed."

***

As she settles into the role of AHA president, what excites Michelle most is the organization's reach.

By addressing issues at every level, the result is healthier communities – all communities.

"AHA leaders not only want to make a difference in the world, they make it happen," she said. "That's what attracts people to the AHA. It's a very dynamic group of folks at the top of their game in every sphere."

She'll continue juggling her many roles at UCSF, as well as her other obligations. That includes spending quality time with her husband, Edward Brown.

They loved traveling pre-pandemic. Nowadays, they venture to waterfront places near where they live in Northern California; Half Moon Bay and Carmel are their favorite hangouts.

One of the fun facts about her personal life is that she's a party planner extraordinaire. The roots of that trace to her youth in Guyana. She's gone from throwing fashion shows as a child with her sister to hosting elaborate tea parties.

"Everyone knows that when they come to my house, there's going to be a well-decorated table," she said.

Beyond her mentors in science, Michelle is inspired by the life of Michelle Obama and the words of Maya Angelou. She's also part of the Beyhive of Beyoncé fans.

Her favorite line penned by Angelou also serves as a fitting description of the way Dr. Michelle Albert leads her own career:

"Try to be a rainbow in someone else's cloud."