Experts recommend lower blood pressure for older Americans

By American Heart Association News

ANAHEIM, California -- The risk of heart attacks, heart failure, strokes and death can be reduced in adults 65 and older if they’re treated for blood pressure the same way younger people are – to a systolic blood pressure of less than 130 – according to new guidelines(link opens in new window) from scientists and medical experts.

Most adults with measurements of 130 for the top number (systolic) or 80 for the bottom number (diastolic) are now considered to have high blood pressure, under guidelines released Monday by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology and nine other health organizations. The treatment standard had previously been 140 for people younger than 65 -- and 150 for people that age and older.

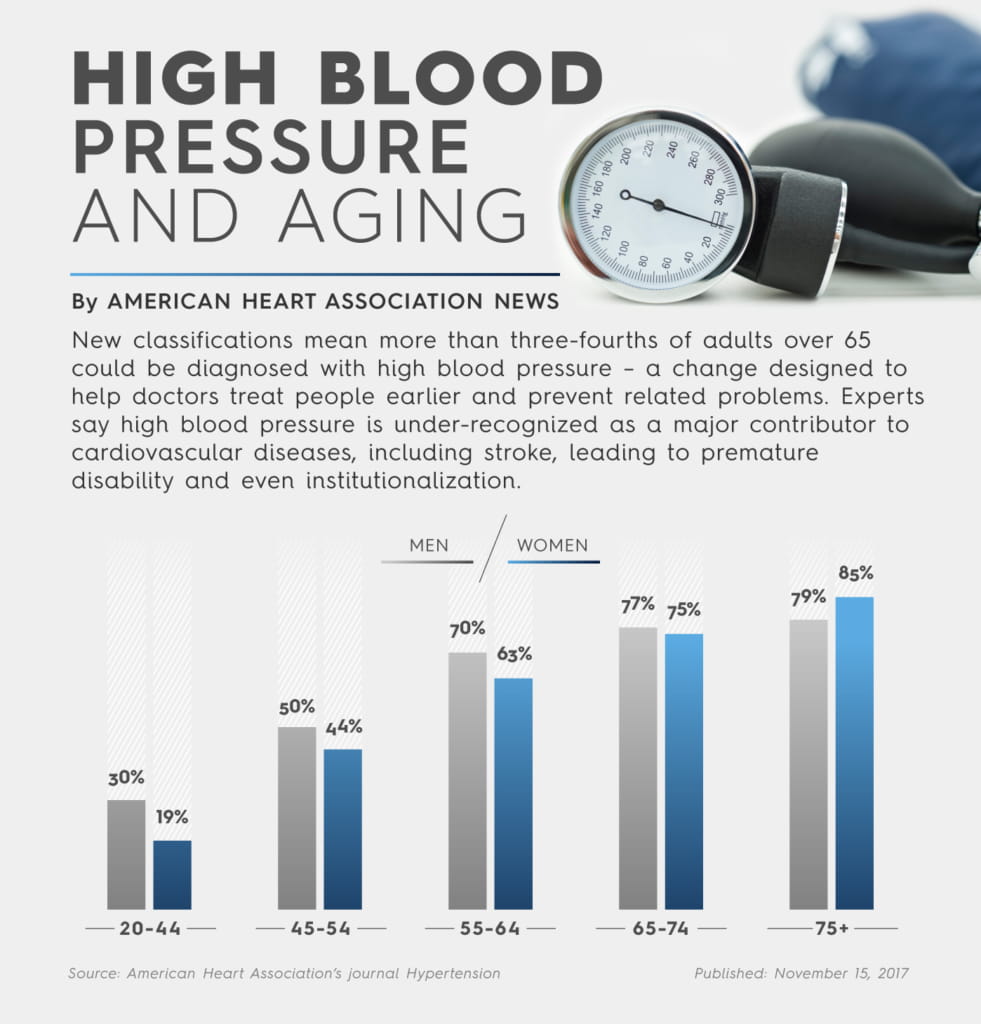

The question of treating blood pressure in older people is complicated by the fact that blood pressure commonly increases with age, so more people at higher ages have the condition. In the past few years, several groups have debated whether lower targets for blood pressure control were effective or even safe for seniors.

Some doctors worried lower pressure levels could increase the number of falls in older populations. A guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians suggested patients older than 60 be treated only to a level below 150/90.

But Jeff Williamson, M.D., chief of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology at Wake Forest University, said a raft of recent studies have shown the benefits of achieving much lower targets for adults who are able to get around on their own and aren’t in a nursing home.

“We know a lot of people in their 70s and 80s are healthier than those in their 60s, and those guidelines put them at risk for complications that would lead to their disability,” said Williamson, who was on the 21-person writing committee for the new guidelines. “You shouldn’t base your therapeutic decisions on age. It should be based on where your patient is [medically]. We shouldn’t deny them evidence-based care just because of their age.”

View text version of infographic

A clinical trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, called the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), studied people 50 and older who had high blood pressure and at least one other risk factor for heart disease.

The study(link opens in new window) found that using medicines to reduce systolic blood pressure, the top number in a reading, to near 120 reduced the combined rate of having a heart attack, acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, stroke or death from cardiovascular disease by nearly one-third. It reduced deaths from any cause by nearly a one-quarter compared to reducing blood pressure to less than 140.

In an analysis that reported the results of the SPRINT trial for people 75 and older, researchers determined(link opens in new window) that lowering blood pressure to a target of 120, compared with 140, also led to significantly lower rates of death and “cardiovascular events” the same as it did for younger people. Because more people at advanced age experience these complications, fewer need to be treated to avoid these adverse effects from high blood pressure.

Because of its “high prevalence in seniors,” hypertension is a leading cause of preventable death, according to the new guidelines. “But, perhaps more importantly, hypertension is under-recognized as a major contributor to conditions leading to premature disability and institutionalization.”

The guidelines acknowledge that treating high blood pressure in older people is “challenging” because seniors have other existing health issues and take other medication that could interfere with blood pressure treatment.

Because there are more complex and varying conditions among older adults, Williamson said it “makes the partnership between the clinician, the provider and the patient all the more important, that there’s communication, so that they can achieve the lowest risk with the highest function.”

For this reason, the guidelines encourage older patients and their health care providers to work together to treat elevated blood pressure. Also, for patients in nursing homes and those with advanced illness and limited life expectancy from diseases such as Alzheimer’s and cancer, the guidelines do not recommend a specific blood pressure goal.

There’s more than just the heart to think about. Helping the cardiovascular system can also affect brain health.

Controlling hypertension and other cardiovascular disease risk factors topped the list of recommendations issued last year by the Institute of Medicine for keeping the brain healthy. And an AHA statement last fall, the result of an analysis of several studies, said high blood pressure is associated with loss of brain function later in life.

Published in AHA’s journal Hypertension, the statement explains how high blood pressure influences brain diseases such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease and vascular cognitive impairment – which includes a range of changes in brain function caused by the decreased blood flow to the brain.

But researchers involved in the statement said clinical trials were needed to show a direct cause-and-effect. The issue has taken on urgency as the number of cases of dementia, which currently affects 30 million to 40 million people worldwide, is set to triple by 2050.

Experts hope an ongoing study called SPRINT-MIND, in which Williamson is involved, will provide some useful data.

The trial is testing whether lowering high blood pressure to a steeper target of 120, helps delay the onset of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. Results are expected by the end of 2018.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected](link opens in new window).